Karate or karate-dō is a martial art of Okinawan origin. Recent research indicates that it developed from a synthesis of indigenous Ryukyuan fighting methods and southern Chinese martial arts. Karate is known primarily as a striking art, featuring punching, kicking, knee/elbow strikes and open handed techniques. However, grappling, joint manipulations, locks, restrains, throws and vital point striking are inherent to the art.

In general, modern karate training is divided into three major areas: basics (“kihon” 基本 in Japanese), forms ("kata" 型 in Japanese), and sparring ("kumite" 組手 in Japanese).

Basic motion (Kihon) ( 基本 ) is the study of the fundamental techniques (punching mechanics, footwork, stances) of the art. This is the 'public face' of the art that most people recognize, ie, the stepping and punching movements.

Kata means 'form' or 'pattern;' however, they are not simply aerobic routines. They are patterns of movements and techniques that demonstrate physical combat principles. Kata may be thought of as fixed sequences of movements that address various types of attack and defense. It is important to remember that they were developed before literacy was commonplace in Okinawa or China, so physical routines were the logical method for preserving a body of this type of information. It is also important to remember that the moves themselves may have multiple interpretations as self-defense techniques- there is no 'standard right or wrong' way to interpret them, but interpretations may have more or less utility for actual fighting. For example, the same passage of a kata may be interpreted as block/punch/block, or joint strike-lock/punch/throw.

Sparring may be constrained by many rules or it may be free sparring, and in modernity is practiced both as sport and for self-defense training. Sport sparring tends to be one hit "tag" type contact for points. Depending on style or teacher, practical aikido and judo-type takedowns and grappling may be involved alongside the punching and kicking.

Many styles of karate also include specialized conditioning equipment, known in Japanese collectively as "hojo undo." Some of the more common devices are the makiwara, the chi-ishi (a kind of off center free weight), and nigiri game (large jars used for grip strength). Some styles also include instruction in kobudo, or traditional Okinawan weaponry. The two arts are not strictly linked, but they have followed a synergistic course of development. It is important to note that kobudo weapons were never used to drive off Samurai by the Okinawan peasantry (Mark Bishop, "Okinawan Karate" )

Meaning of the word karate

The word "karate" originally comes from the Okinawan pronunciation of the kanji characters "kara"( 唐 ) which means Tang dynasty or simply China, and "te"( 手 ) meaning hand:

The meaning of "Chinese hand" or "Tang hand," “Chinese fist” or "Chinese techniques," reflected the documented Chinese influence on Karate. Following Japan's invasion of eastern China in 1933, Gichin Funakoshi (known as the father of modern karate) began using a homonym of the kanji character "kara" by replacing the character meaning "Tang Dynasty"( 唐 ) with the character meaning "empty"( 空 ). This followed the so-called Meeting of the Masters in October of 1936, which included Chojun Miyagi, Chomo Hanashiro, Kentsu Yabu, Chotoku Kyan, Genwa Nakasone, Choshin Chibana, Choryo Maeshiro and Shinpan Shiroma (Gusukuma). Since this 1933-1936 period, the word pronounced "karate" has almost universally referred to the written kanji characters meaning "empty hand"( 空手 ) rather than "Chinese hand"( 唐手 ). It is also probable that this change originated several years earlier in Okinawa, since Hanashiro Chomo uses the "empty hand" writing form already in his 1905 publication "Karate Shoshu Hen".

The term "empty hand" has often been interpreted as containing Japanese Zen principles that go beyond the obvious inference that the practitioner carries no weapon. The Zen process of emptying the heart and mind of earthly desire and vanity for oneself through perfection of one's art. Some readings of this new ideogram refer to rendering oneself empty or egoless, leading to further development of spiritual insight. Funakoshi stated that the actual meaning of his writings are as follows: "As a mirror's polished surface reflects whatever stands before it and a quiet valley carries even small sounds, so must the student of Karate-Dō render of their mind empty of selfishness and wickedness in an effort to react appropriately toward anything they might encounter."

Although such philosophies have been inspirational to many generations of karate students; removing an explicit reference to China in the art's name may have been a politically shrewd move more than anything else given the nationalistic political climate of Imperial Japan in the 1930s.

The "do" suffix is used for various martial arts that survived Japan's turbulent transition from feudal culture to "modernity," and implies that they are not just techniques for fighting, but have spiritual elements when pursued as disciplines. In this circumstance it is usually translated as "the way of" (cf. Aikido, Judo and Kendo). Thus, "karate-do" is "the way of the empty hand".

Etymology

As the below history discussion should make clear, this can be a difficult and sometimes inflammatory question, complicated by attitudes toward philosophy and competition, by questions of lineage and primacy, and perhaps above all by questions of nationalism and identity. The term Karate has become somewhat generic in the West, where one even sees signs for "Filipino Karate" and the like because of the name recognition of "Karate". There are at least three ways to look at the question:

- Etymologically, Karate is currently written as 空手, "empty hand".

- Etymologically, Karate was originally written as 唐手, "Chinese hand" or "Tang fist," and is thus any art which can trace its descent from the Okinawan Karate styles.

- Karate is any striking art which calls itself Karate.

History

Karate has been and continues to be a multi-cultural development, absorbing the contributions of many gifted practitioners over time and crossing many borders. Compiling a reasonably accurate history of Karate is challenging.

Contrary to popular belief and established myths, the development of Karate did not move from India, to China to Okinawa via a wandering monk named Bodhidharma. Although Bodhidharma is a historically verifiable person who might have brought Ch'an Buddhism to China, the development of the Asian fighting arts had nothing to do with him. The association of Bodhidharma and karate has more to do with pulp fiction novels and movies than real life (Guo, Kennedy: "Chinese Martial Arts Manuals: A Historical Survey" ).

Karate's Origins in Okinawa

Japan annexed the nominally independent Ryukyu island group in 1874 after centuries of strong Japanese influence over the kingdom's affairs. The relationship between Okinawa and Japan is complicated. For purposes of discussing Karate, it is convenient to speak of Okinawa and Japan as separate entities. The question of whether Karate is Japanese or Okinawan is somewhat akin to asking whether the luau or the hula dance are American traditions or Hawaiian ones: They developed in Hawaii prior to when Hawaii became one of the United States, and so are usually described as Hawaiian, not American. The case is similar for Karate, which is originally of Okinawan origin.

Karate is a mixture of indigenous Okinawan fighting arts "Ti" ("Te" in Japanese) and empty-handed Chinese kung fu, the latter having been brought to Okinawa by political envoys, merchants, and sailors to and from Fujian Province.

The Okinawan martial art "Ti" was practiced by Okinawa royalty and their retainers for centuries before, and alongside, later Chinese influences. For the most part there were no particular styles of "Ti", but rather a network of practitioners with their own individual methods and eclectic traditions. Early styles of karate are often generalized as Shuri-te, Naha-Te and Tomari-te, named after the three cities in which they emerged, although these are not concrete distinctions. Each area (and the teachers who lived there) had particular kata, techniques, and principles that distinguished their local version of "Ti" from the others.

Members of the Okinawan upper classes were sent to China regularly to learn and study a variety of disciplines, political and practical; this exchange was not too different from the practice of exchange students today. The incorporation of empty-handed Chinese kung fu occurred partly because of these exchanges. Estimates of the Chinese influence in modern Karate styles (or schools) vary considerably, and there are no clean divisions among 'styles'. To this day Karate styles from some areas bear a striking resemblance to Fujian martial arts such as Fujian White Crane, Five Ancestors, and Goroquan (Hard Soft Fist, pronounced "Gōjūken" in Japanese), while some karate looks distinctly Okinawan.

In 1806, "Tode" Sakukawa (1782-1838), who had studied pugilism and staff (bo) fighting in China (according to one legend, under the guidance of Koshokun, originator of kusanku kata), started teaching a fighting art in the city of Shuri that he called "Karate-no-sakukawa." This was the first known recorded reference to the art of Karate ( 唐手 ) in a modern form. The word "Kara" ( 唐 ) referred to China itself, and "Te" ( 手 ) meant hand, in the sense of a style of fighting; so Karate meant "the Chinese techniques" or "Tang Hand".

Around the 1820's, Sakukawa's most significant student, Sokon Matsumura(1809-1899) taught a synthesis of te (Shuri-te and Tomari-te) and Shaolin (Chinese 少林 ) styles. It would become the style Shorin-Ryu ("Pine Forest" ).

Matsumura taught his karate to Anko Itosu(1831-1915), among others. Itosu adapted two forms he learned from Matsumara, namely kusanku and chiang nan, to create the Ping'an forms ("Heian" or "Pinan" in Japanese, as the symbols can be read differently) as simplified kata for beginning students. In 1901 he was instrumental in getting karate introduced into Okinawa's public schools. These forms were taught to children at the elementary-school level. Itosu is also credited with taking the large Naihanchi form ("Tekki" in Japan) and breaking it into the three well-known modern forms Naihanchi Shodan, Naihanchi Nidan and Naihanchi Sandan.

Itosu's influence in Karate is very broad. The forms he created for beginners are common across nearly all forms of Karate. His students included some of the most well-known Karate practitioners, including Gichin Funakoshi, Kenwa Mabuni, and Motobu Choki. He is sometimes known as the "Grandfather of Modern Karate."

In addition to the three early "Ti" styles of Karate, a fourth "Okinawan" influence is that of Kanbun Uechi (1877-1948), who, at the age of 20, went to Fuzhou in Fujian Province, China, to escape Japanese military conscription. While there, he studied under the leading figure of Chinese Nanpa Shorin-ken at that time. He later developed his own style of Karate and brought it to Japan, though the style itself was neither taught in Okinawa nor rooted in Okinawan "Ti".

Characteristics

Okinawan Karate shows the distinctive emphasis on forms training that characterizes Karate as a whole; also the method of twisting the hips to generate power and tensing the body at the moment of impact to focus power called kime. The more experienced the Karateka, the shorter the kime, and the kime is done as much with ki (chi) as very short physical contraction of the muscles when done properly. The stances in Okinawan styles are often higher than seen in Japanese styles of Karate, and somewhat looser. The Okinawan practitioner will sometimes rise while stepping, and then settle into stance; the knees retain some flex or bounce when in stance.

The History of Karate in Japan

Masters of Karate in Tokyo (1930s)

(From left)Toyama Kanken, Ohtsuka Hironori, Shimoda Takeshi, Funakoshi Gichin, Motobu Choki, Mabuni Kenwa, Nakasone Genwa and Taira Shinken

Funakoshi, father of Shotokan karate, is generally credited with having introduced and popularized karate on the main islands of Japan. He was a student of Anko Asato and Anko Itosu, who had worked to introduce karate to the Okinawa Prefectural School System in 1902. He brought Itosu's Pinan kata to Japan (as did other of Itosu's students, such as Kenwa Mabuni, founder of Shito-ryu karate). Funakoshi worked specifically to introduce modernizations into karate and to spread it to Japan. However, there were many other Okinawan karateka living and teaching in Japan during this time period. Funakoshi's peers included such notable figures as Kenwa Mabuni, Chojun Miyagi, Motobu Choki, Toyama Kanken, Kanbun Uechi and several others.

This was an especially turbulent period in history for that area of the world, including Japan's official annexation of the Okinawan island group in 1874, the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), and the rise of Japanese expansionism (1905-1945). The Karate styles within Japan have fairly clean lineages; but any assessment of how Karate crossed borders in this period is complicated by issues of nationalism, the historic Japanese racism faced by non-Japanese Asians, and the typical resentment of occupied peoples toward a conqueror. Many recognizeable offshoots of Karate, particularly in Korea, deny the name because of nationalistic ideals and the word's association with Japan; likewise, some obvious offshoots of Karate are disowned by Japanese practitioners, perhaps because of a Japanese preoccupation with primacy or purity.

Japan was occupying China at the time, and Funakoshi knew that the art of Tang/China hand would not be accepted; thus the change to 'way of the empty hand.' The "do" suffix implies that karatedo is a path to self knowledge, not just a study of the technical aspects of fighting. Like most martial arts practiced in Japan, karate made its transition from -jutsu to -do around the beginning of the 20th century. The "do" in "karate-do" sets it apart from karate "jutsu", much as aikido is distinguished from aikijutsu, judo from jujutsu and so on. The name change also served to familiarize a foreign tradition during a time of fervent Japanese nationalism.

As mentioned, Funakoshi changed the names of many kata and the meaning of the art itself (at least on mainland Japan). He most likely did this to get karate accepted by the Japanese budo organisation Dai Nippon Butoku Kai. Funakoshi also gave Japanese names to many of the kata. The five Itosu Pinan forms became known as Heian; the three Naihanchi forms became known as Tekki; Seisan as Hangetsu; Chinto as Gankaku; Wanshu as Empi; etc. These were mostly just political changes, rather than changes to the content of the forms although Funakoshi did institute changes to the content. The name changes may have been designed to make the art sound more Japanese (less "foreign" ). Funakoshi had trained in two of the popular branches of Okinawan karate of the time, Shorin-ryu and Shorei-ryu. In Japan he was influenced by kendo, incorporating some ideas about distancing and timing into his style. He always referred to what he taught as simply "karate"; however, in 1936 he built the Shotokan dojo in Tokyo, and the school or style he left behind is usually called Shotokan.

The modernization and systemization of karate in Japan also included the adoption of the ubiquitous white uniform which consisted of the kimono and the dogi or keikogi - mostly called just Karategi (pronounced 'gey' like 'key') - and colored belt ranks. Both of these innovations were originated and popularized by Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, one of the men Funakoshi consulted in his efforts to 'modernize' karate. Ranking systems and their values differ greatly from organization to organization, which sometimes leads to confusion when trying to determine a relative standard for karate training and credibility. It is not uncommon to see Westerners claiming absurdly inflated ranks (Grand Master, Great Grand Master, Soke, etc...) Photos of early Okinawan practitioners show students in the street clothes of the day, or sometimes in undergarments. A student trained under a teacher for years, without any sort of tangible advancement other than development of skill.

Styles

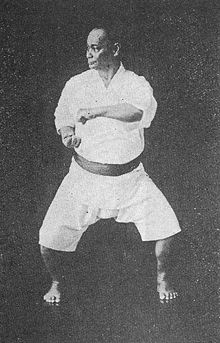

Motobu Choki in Naifanchi-dachi, one of the basic Karate stances

Within karate there are presently a multitude of different styles or schools. These include:

(A-Z)

Many organizations offer hybrids of karate styles.

Full contact karate includes Kyokushin-kaikan, which was founded by Masutatsu Oyama, and other offshoots of Kyokushin such as Ashihara, Shidokan, and Seido to name but a few; they are considered full-contact because emphasis in matches is placed on the amount of damage done rather than the quality of technique displayed. Most full contact karate styles or organizations have developed from Kyokushin karate. Kansui-ryu is a full contact karate style which has developed independently of Kyokushin, while having a number of similarities.

Influence of Karate in Korea

Japan annexed and occupied Korea from 1910 until 1945. Koreans who were able to travel to Japan during the occupation, often for education, became exposed to Japanese martial arts. After liberation from Japanese colonialism and following the turmoils of the Korean War, many of the martial arts schools in Korea were started by masters trained in Japanese Karate with varying degrees of training in Chinese and Korean martial arts. In 1955, at the behest of President Syngman Rhee, the dozens of Korean martial arts schools were standardized and the resulting construction became Taekwondo. Although major techniques of Taekwondo largely differed from Japanese Karate as they were centered around kicks from indigenous arts such as Taekyon, Karate's influence was nonetheless significant. For example, the earliest forms called Poomse were adopted entirely from Karate as well as the belt and degree system.

The History of Karate in the United States

Traditional Karate entered the United States principally via those members of the military who learned it in Okinawa or Japan and opened schools upon their return to the United States. For example, Robert Trias is often credited with opening the first Western Karate school in the United States in Phoenix, Arizona in 1942, though some historians note that Ron Keiser instructed a number of his fellow Americans in his family's Karate tradition while imprisioned in a Japanese-American internment camp. Although there are many who claim to be the "founder" of American karate, or to have made fantastic innovations/studied with esoteric unknown Asian masters, these claims are impossible to verify, and have little to do with actual karate.

Karate Internationally

Since the 1950s, Karate has exploded in popularity worldwide. By the end of the 20th century, Karate was one of the most pervasive cultural exports from the Far East to the Western world. It is impossible to enumerate the various schools and styles worldwide, that are identifiably "karate". Nowadays one can learn Karate (or one of its offshoots) almost anywhere. It is no longer something practiced in just certain countries: Karate is universal. There were two main avenues for the propagation of Karate to the rest of the world:

- Allied servicemen, stationed in Japan and Okinawa after 1945, who studied Karate and returned to their home countries.

- The emigration of Karate masters from Japan or Okinawa to other parts of the world, where they taught their art.

Another factor in the enduring appeal of Karate is film; kung fu movies have propelled karate and other Asian martial arts into mass popularity. Some well-known stars who were students of Karate or related styles are:

An additional factor in the interest in Karate is the availability of international competitions. There are bodies which sponsor competitions, including the U.S. Karate Association and Professional Karate Association.

Japanese Karate does not have Olympic status, although it received more than 50% of the votes to become an official Olympic Sport; 75% of the votes are required. The World Karate Federation (WKF) is the recognized International Sport Federation by International Olympic Committee (IOC) for Karate. WKF represents the major uniform rules among all styles. Karate activities in individual countries are organized through national karate federations, recognized by each official national sports governing body and a National Olympic Committee. Each continent has one federation for continental karate activities. There are many organizations on national and international Karate organization, regarding competitive activities and styles activities. Only WKF, however, is recognized by the International Olympic Committee, and only one in each country is linked with that official structure. For that, official recognition of the country sports governing body is required. Each country organizes their own karate championships following WKF rules.

Japanese Karate competition can be in three disciplines: sparring (kumite), forms (kata), or kobudo (weapons) kata (weapons however, are technically not karate); competitors may enter either as individuals or as part of a team, or both. Evaluation for kata is done by a panel of judges; sparring is judged by a head referee and two to four side referees. Sparring matches are often divided by weight classes.

Some traditionalists are concerned that the emphasis on competition is antithetical to the deeper values of the art. They feel that sport competition promotes a highly compromised interpretation of the art, including point fighting and demonstration of forms for entertainment value. Forms are often set to music, and weapons that light up or glow are sometimes used. In extreme cases, martial practicality is eschewed in favor of gymnastics. Traditionalists feel this should not be regarded as emblematic of karate; others feel the publicity is helpful.

Karate Sparring

Famous British karate competitor Frank Brennan defeats an opponent with an ippon technique

There are a number of ways of scoring matches, including sanbon kumite, and shobu ippon kumite. In sanbon kumite (3 point fighting), the matches usually last until time, unless the tournament has a mercy rule in place. Kicks to the head are worth 3 points, kicks to the body worth 2, and hand techniques worth 1. A sweep followed by a technique that lands is worth 3 points. This is the method most often used in tournaments, as it promotes flashier fighting that is better suited to spectator sports. In shobu ippon kumite (one point fighting), the fights last until one person scores a point. A point in ippon kumite is any technique that would have been killing or disabling if landed with full force instead of the moderated contact used in practice. A half point (waza-ari) is any technique that would have caused considerable harm. This is also the system used by olympic judo. Ippon/wazari kumite promotes a more conservative style of fighting, more like actual fighting, as a single mistake can end the match.

Styles branching from Mas Oyama's kyokushinkai school of karate practice knockdown kumite. In this form of competition, the match is won by flooring the opponent with a strike. Punching to the head is forbidden in knockdown tournaments, but punches to the body and kicks to the head, body or legs can be thrown with full power. This promotes more aggressive fights than the somewhat cautious style favoured by shobu ippon kumite competitors.

A further development to this theme is practiced by daido juku karate tournaments in which participants wear helmets covering their face and head, but there are very few banned attacks (headbutts, punching to the head, grappling and kicks to the shins are permitted, for example). Here, a match can be won by making an opponent submit as well as by knockdown.

Karate and Character

In keeping with the -do nature of modern Karate, there is a great emphasis on improving oneself. It is said that there is no first strike in Karate, meaning, among other things, that the art is for self-defense; not injuring one's opponent is the highest expression of the art. Many people study Karate for self-improvement.

- "The ultimate aim of Karate lies not in victory or defeat, but in the perfection of the character of its participants." -- Gichin Funakoshi

- "The Way is not meant as a way of fighting. It is a path on which you travel to find your own inner peace and harmony. It is yours to seek and find." -- Hironori Ohtsuka

"karate always begins and ends with rei." respect is a very important part of karate, it is about cleansing oneself and stregthining character. The spirit of "osu" is to push onself to the limit of one's ability, to persevere under pressure, to endure.

In many forms of karate a KIAI! (spirit shout) is used when completing techniques in training. The KIAI is a shout generated by sharp exhalation of air from the lungs via the contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles. The idea of the KIAI is to focus the mind and body and bring it into one, the technique is preformed by the mind and body at the same time to deliver a powerful attack or defence

Belt colours

Originally, Karate training did not involve any notions of rank. After introduction to Japan, some adopted only 3 obi (belt) colours. White, Brown and Black, with several ranks of each. This is the same color system that was used by the Kodokan. Gichin Funakoshi adopted the idea from Jigoro Kano. Here is the original belt system, still used by Shotokan Karate of America:

- Ungraded - white

- 8th kyu through 4th kyu - white

- 3rd kyu through 1st kyu - brown

- 1st dan and above - black

As karate became more widespread, a decision was made by some karate organizations to add more colors and ranks to the system.

One example is given below, but these vary among organizations.

- 9th kyu - red

- 8th kyu - yellow

- 7th kyu - orange

- 6th kyu - green

- 5th kyu - blue

- 4th kyu - purple

- 3rd kyu - brown

- 2nd kyu - brown

- 1st kyu - brown

- 1st to 5th (or all levels of black) dan - black

- 6th to 8th dan - red with white stripes

- 9th and 10th dan - red

The requirements for each belt vary as a student progresses, and each form of karate has a different grading system, however it is commonly noted that the progression of learning is in the following order: 1. Position - Stance 2. Balance - Control of position 3. Co-ordination - Control of balance and position in technique 4. Form - Performing the above correctly 5. Speed - Increase the rate of performance without loss of form 6. Power - Strengthening the techinique 7. Reflex - The technique becomes a natural movement 8. Conclusion - It is essential that the progression is not rushed, but developed at each stage. |